Beijing’s war on terror is reining in Christians, adding to fears that its mission is not only to stamp out Islam, but also to strike hard at the Uyghur nation itself.

Ruth Ingram

Uyghur mothers don’t usually teach their daughters to cook. They prefer to leave the task to the mother in law of the new family their child will eventually marry into. But Gulhumar Haitiwaji, now a French citizen, has been on a fast learning curve since her mother’s disappearance. Just over two years into her own marriage, she now has two homes to cook for since Gulbahar, 52-year-old wife and mother of two, went missing during a visit to North West China’s Xinjiang region, from their adopted home in Paris in November 2016. It is now more than two years since a brief holiday back to their homeland to sort out her affairs, became a nightmare of disappearance and foreboding. Only finally last December did they get news. But it was not good. Their worst fears were realized after learning that she had been sentenced extra-judicially to seven years in prison for treason.

Kerim Haitiwaji, the husband of Gulbahar, apologizes profusely for the state of their home. Despite everything meticulously in its place, he is bereft without his wife. His life has been put on hold since her disappearance. An Uber driver during the day, he spends hours at night pouring over the news coming out of his homeland. “I can’t concentrate on anything else these days,” he says. “I am lost without my wife.”

27-year-old Gulhumar chops the vegetables meticulously putting them in separate piles ready for frying and talks about her mother’s disappearance. She alternates between depression and anger. At first afraid to speak out because of repercussions towards relatives back home, the family decided to bring the injustice into the open once the prison sentence was confirmed. “She is just an ordinary woman. She is educated. She speaks Chinese. She has never harmed the Chinese state. Why would they say she has betrayed her country?” She asks rhetorically.

Methodically cutting the celery, tomato, garlic, beans, pepper, and potato into bite-sized lozenge shapes, just as her mother might have done, she has already prepared the raw dough for noodles placing it in circular swirls on a metal plate. She hasn’t quite mastered the art of beating them out by hand and leaves this to her husband who claims to be an expert. In half an hour it is ready.

“Laghman” – the national dish of the Uyghur nation whose native population lives in a vast sparsely populated area two and a half times the size of France, more than 3,000 kilometers from the capital on the other side of China. They co-exist uneasily with the majority Han Chinese chafing against rule from Beijing making them unpopular with their far-away leaders.

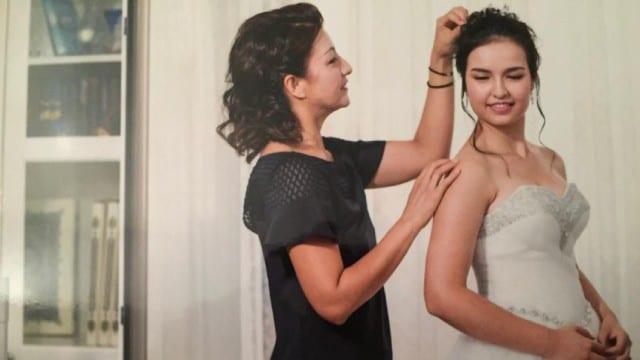

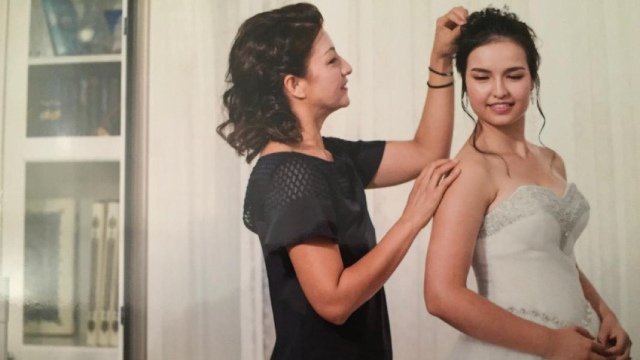

We devour the delicious bolognese with her father who takes a French baguette and breaks it into several pieces, in place of a circular nan bread which would have been the sine qua non of dishes back in Xinjiang. “We’ve become Frenchified,” he says with a rare smile. He arrived in France as a refugee 15 years ago, and Gulbahar and the girls followed in 2006. Gulhumar was 14 and Gulnigar, her younger sister, was 8. Now fluent in French, Chinese, and their national Uyghur language, they love their new homeland. Gulhumar studied marketing at university and now sells upmarket jewelry, and her younger sister is an economics undergraduate in Paris. The family has been well looked after by the French government and live in a large 2-bedroomed state-subsidized apartment with underground car parking.

We eat the laghman with chopsticks, glued to Arte, the European Culture channel which has briefly turned its attention to the atrocities emanating from North West China. Estimates are emerging of between 1-3 million Uyghurs who are either enduring ex-judicial prison sentences or indeterminate periods of re-education in vast camps, purpose-built according to the Chinese government to “eradicate the tumors” of terrorism, separatism, and religious extremism.

Gulhumar has just returned from the Arte studio where she spent ten emotionally grueling minutes on camera detailing the fate of her mother who visited Xinjiang back in November 2016 and within days of her arrival was forced to surrender her passport to the police. She had merely returned briefly to attend to her pension and visit ailing parents, but after the confiscation of her passport which she assumed was connected with her pension, she was left in limbo unable to leave the country. Two months later on receiving a summons from the same police station, she assumed all would be clear to return to France, but instead she found herself in a cell looked after by stony-faced armed officials and no passport. It seemed that the call home, ostensibly to sign pension documents had been engineered by her work unit to trap her. She managed to get a message out to the family, but this was the last time they would hear from her. On January 29, 2017, she disappeared without a trace.

In July 2017, they heard she had been taken to a transformation through education camp, but there were twenty more agonizing, silent months before Christmas last year when news finally came through of the draconian sentence that had been handed down. There had been no court case that they were aware of, no legal representation and no formal notice to the family of the verdict – just word of mouth. The heartbreaking message was passed on by phone by a friend of the family.

“On one hand, it was a relief,” says Gulhumar. “At least we knew she was alive.” But as the days passed after hearing the news, the outrage and grief increased to such an extent that the family determined to publicize the fate of their mother who they believe is innocent of the charges. “She is a housewife and mother. She has never betrayed her country and is no terrorist,” she says. They are hoping that pressure brought to bear diplomatically might secure her release.

A cynical twist to her mother’s fate is her arrest amid the clampdown in Xinjiang aimed primarily at Muslim Uyghurs and so-called extremist Islamic ideology. The strike-hard policies are cloaked with language attacking Islamic fundamentalists, the end goal of which is to eradicate religious extremism at its roots and prevent its spread “like an incurable malignant tumor” (from an official Communist Party audio recording, which was transmitted in 2017 to Uyghurs via WeChat, a social-media platform). “The irony of all this is that my wife isn’t even a Muslim,” says Kerim. “She converted to Christianity several years ago and eschews violence. Our faith tells us to pray for our governments and leaders. We must forgive those who persecute us and turn the other cheek. There is no reason to imprison her. She is not a danger to China.”

On hearing the verdict, Gulhumar quickly compiled a petition which she released online hoping to generate interest in her mother’s cause. So far, more than 436,000 people from around the world have signed. A human rights lawyer has stepped forward to plead the case, and the next step is to present it to President Macron. Their vain hope is that it might carry some weight with Beijing. “I just want our mother back,” she says tearfully.

A major problem as far as leverage from Paris is concerned is that despite father and both daughters having become French citizens, Gulhumar’s mother never surrendered her Chinese passport. “She had all the papers ready to apply, but because her elderly parents were still in Xinjiang it seemed more convenient to wait, just in case she needed to return in a hurry,” said Kerim. “There didn’t seem to be any rush.”

They could never have anticipated the rapid deterioration in the situation for their people once a new leader, Chen Quanguo, fresh from quelling dissent in Tibet was appointed to do the same among the Uyghurs in August 2016. They underestimated the Orwellian changes which would immediately take effect in their homeland under his iron fist. Within one short year, Chen’s draconian hand had transformed the security temperature in the largely Muslim majority region from tepid to torrid, and they could not have foreseen the danger that their mother was walking into.

But Gulbahar Haitiwaji’s story is not rare. While the family conducts a high-profile campaign for her release, Paris is full of thousands of Uyghurs whose own tragedies are unfolding. Their brief sojourn overseas has unwittingly made them candidates for re-education or worse on arrival back in their homeland, and Karim estimates that while 500-600 already have refugee status, there are also 3,000 students stranded in France, too terrified to speak out in case their families suffer at home and scared stiff of returning. Their source of income has dried up since new laws forbid money leaving China, and all of them are gazing into an uncertain future not planned or envisaged. Others who have put down roots, many of them refugees, have formed a French branch of the World Uyghur Congress. They are all without exception outraged at the events unfolding in their region. All have tales of relatives and friends who have disappeared. Most have lost touch with dear ones at home for fear of the dangers to them of overseas contact.

Meanwhile, Kerim and his daughters had no idea where Gulbahar was. Despite occasional one- or two-word reassurances via the Chinese social media platform WeChat from Gulbahar’s sister who claims she or her mother are visiting once a month, Gulhumar is not convinced that they are being told the truth. “My aunt tells us she is eating meat and that she is well,” she says. “But this is ridiculous and goes against all the reports coming out of the camps from a trickle who have been released, usually because of ill health. These are lies told by her sister who has to put on a brave face,” she says. She worries that her mother is even alive. “Everyone in Xinjiang has to save their own skins,” she says. “How do we know what is really happening to our mother?” Gulhumar says that she is worried too about her mother’s health. “She has high blood pressure and needs daily medication following surgery to remove a tumor in her breast two years ago. Without this prophylactic treatment who knows what might happen,” she says, explaining that she had heard there was little or no medical care in the camps.

As the days go by without news of their mother’s whereabouts, Gulhumar is heartened by international support she has received and the number of signatories to her petition which increases every day. They cling onto a faint chance that President Macron and his aides might gain the ear of Beijing. Only this week a French government representative who had been in touch with the Chinese consulate in Paris, got in touch with the news that Gulbahar is alive. It is possible that the international exposure given to this case might have embarrassed Beijing into re-viewing her case. “The officials said that police are still investigating the complaint against her two years into captivity,” said Kerim. Despite tentative reassurance, the family is not holding its breath until she is returned to French soil. Gulhumar hopes that one day soon her mother might be able to enjoy her cooking. “I look forward one day to making her laghman, and we can eat together once again as a family,” she says longingly.

(The photos for the article have been provided by the Haitiwaji family).

Go to Source

Author: Ruth Ingram